Australia Day and the Hollowness of Identity Politics

When movements care about status more than people

Last month, Australia subjected itself to the latest iteration of its national holiday, prompting a familiar round of national acrimony and agitation over the explicit association of January 26 to Australia’s colonial origins.

As is now custom, hundreds of thousands of Australians took to the streets of the capital cities in order to protest against the Date, in repudiation of the idea that Australia should celebrate the day the British flag was raised over Botany Bay, and in accordance with the idea that Australia’s history is a source not of pride, but of shame.

As such, colonial monuments were vandalised; Captain Cook was torn down; Australians were warned: the colony will fall.

Such extreme displays of ‘anti-Australia’ sentiment, which were not the norm 10 or 20 years ago, are a symptom of a deeper and somewhat radical change in the way a growing number of Australians understand questions of identity and history.

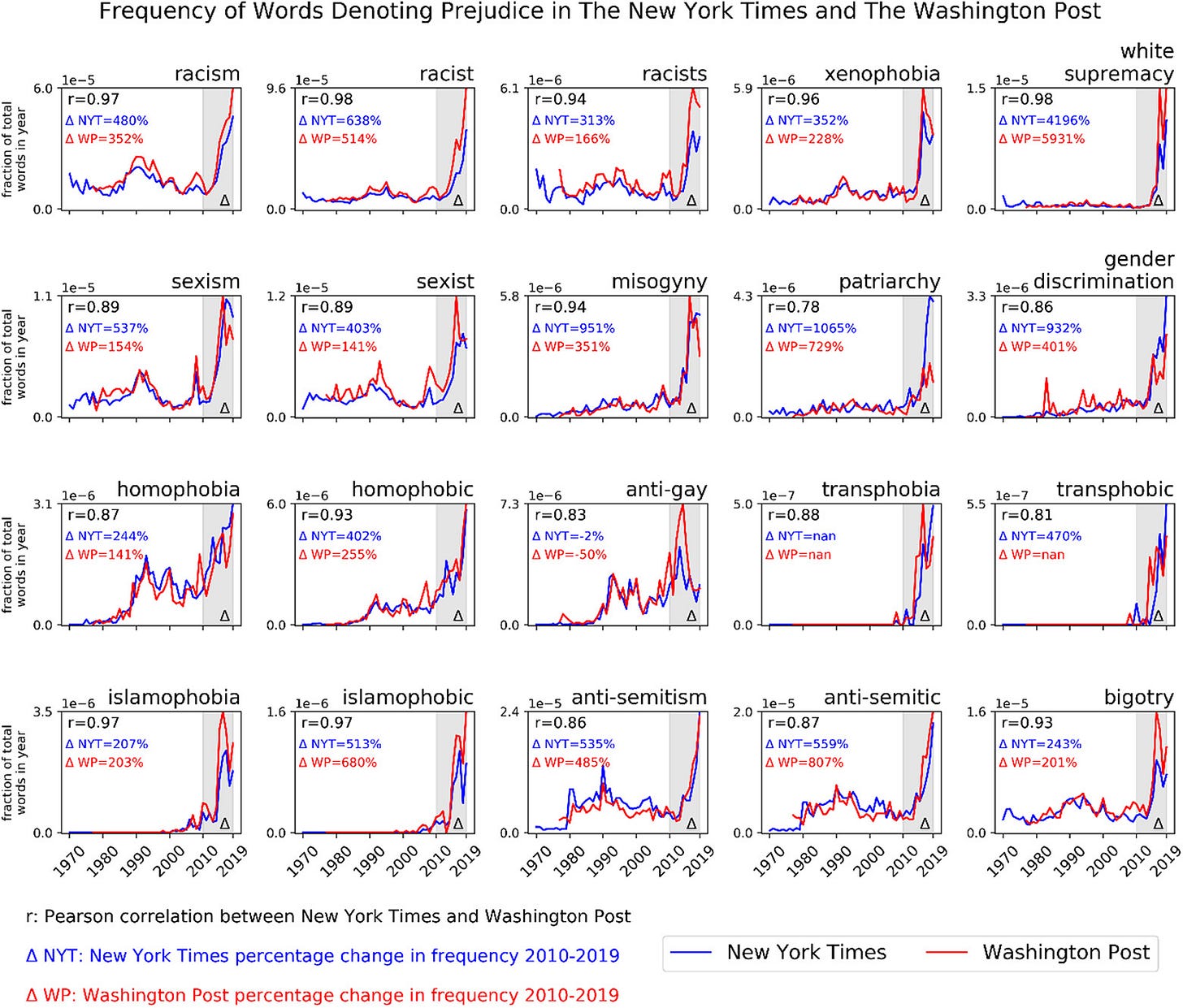

In fact, this generational shift fits within a broader ideological phenomenon which has greatly impacted the domestic politics of Western countries since the 2010s until the present day. This phenomenon has been identified and labelled, for want of a better term, as the ‘Great Awokening’.

The ‘Great Awokening’ refers to the discernible radicalisation in the way young, university educated Westerners- and therefore by extension, the media- perceive issues of race, gender, culture, and identity, leading to the contemporary pre-eminence of what we now know as ‘woke’ identity politics.

Australia’s performance of the ‘Great Awokening’- while in most part plagiarising the language and ideas of the USA- has taken on a distinctively antipodean character reflecting the country’s primordial colonial guilt. Thus, the sudden surge in the early 2010s of popular energy and momentum behind ‘Invasion Day’ protests in Australia can only be properly understood when situated within the broader context of ideological turmoil permeating the country and the broader Western world.

Reflecting this trend, a growing number of Australians now refuse to celebrate Australia Day, and nearly all large employers- including the public service- offer their staff the opportunity to ‘live their values’ by working rather than holidaying on January 26. This retreat from patriotism- led by white collar Australians- has found a welcome home among those who already viewed flag-waving patriotism as declassee.

As a result, even though the day currently enjoys majority public support, the future of Australia Day as a national holiday appears increasingly uncertain. There is a growing sense that the fracas it engenders makes the national holiday unviable, and that it will one day be changed, public preference be damned.

With this socio-political context out of the way, I would like to delve into the core theme of the essay in earnest.

What I find the most interesting about the Australia Day debate is less the debate itself than the meta-politics of the issue, and what it reveals about contemporary identity politics.

My time teaching in Tennant Creek was a formative experience, not least for the vantage point it has provided in observing the frequently absurd way Indigenous issues are discussed.

One of the most fundamental absurdities that Tennant Creek illuminates about the national discourse, is that it is almost entirely disconnected from the concerns and interests of the most marginalised Indigenous Australians in the country.

No event shines greater light on this disconnect than the Australia Day debate.

Come January 26, a slew of media coverage will be devoted to conveying the impression that the date represents a deeply painful day of mourning for all First Nations people. While this may certainly be true of the Aboriginal people who tend to be represented in the media, this is just not the case for the Indigenous residents of Australia’s remote interior.

There, Australia Day is largely a non-event.

I remember one day in class asking my secondary school students what they thought about Australia Day. Contrary to the assumptions of many, the students expressed nonplussed bemusement at the question- because they didn’t even know the question’s context.

The Indigenous residents of remote Australia, by and large, do not have the inclination or the luxury to care about symbolic culture war issues like Australia Day- moreover, they do not even conceive of the day as a political event, let alone as problematic.

This illustrates a simple truth of contemporary Australia, which is that the deeper into the bush you go, the less people are animated by or even conscious of the raging culture war debates which animate the residents of Australia’s capital cities.

We thus find ourselves in the curious position where contemporary Aboriginal activists, in choosing to focus on symbolic issues like Australia Day, are overlooking the more fundamental concerns of the most disadvantaged Aboriginal people in the country.

Why Indigenous activists avoid talking about real issues

It might seem sensible to suggest that middle-class Indigenous activists should choose to focus on more bread-and-butter issues affecting the lives of disadvantaged Indigenous Australians, rather than on symbolic issues like Australia Day.

This misunderstands the psychology of identity politics.

Activists don’t want to talk about the issues afflicting remote communities.

Bringing attention to the specific problems of remote communities makes identity activists uncomfortable (to the extent that they are even aware of them), because these problems do not easily reconcile with their preferred and proffered model of the world.

When obliged to address the specific issues of Indigenous communities, Indigenous identity politics functions by:

a) denying the existence of social problems that are concentrated in Indigenous communities, or the legitimacy of talking about them; or

b) framing those problems as the causal responsibility of white Australia.

This boils down to one reason: identity politics is fundamentally about advancing the symbolic status and self-esteem of the collective group, rather than advocating for people’s material, objective, and mundane interests.

This also explains why practitioners of identity politics (around the world) are so concerned with ‘gaps’ in outcomes between groups in the way they are, as if it were a contest. It is not primarily out of concern for the actual welfare of people, but out of a sense of insecurity for the status of the group.

For practitioners of Indigenous identity politics, this looks like campaigning on symbolic issues like Australia Day, which represents the push for an ‘Indigenous-first’ conceptualisation of Australian identity, or pushing for the acquisition of group-based political power and status, like the Voice to Parliament.

Of course, this occurs under the pretext- sincerely held to varying degrees- of addressing Indigenous Disadvantage. However, in these instances Indigenous Disadvantage is only ever framed and discussed in the abstract, as it is only in this way that it can serve its purpose as potent rhetorical weapon with which to garner political concessions.

To raise attention to specific issues is not in activist interests, because the more one learns about these issues, the less convincing activists’ solutions seem.

To illustrate with a real example: Endemic domestic violence in remote Indigenous communities. It exists, but it looks bad, so the activist’s solution is basically not to put too much energy into drawing attention to it, to discount the agency of Aboriginal people by appealing to absolving factors like intergenerational trauma, or to simply deny the issue altogether.

The flip-side of this dynamic is that conservatives are generally happy to highlight such issues, because of the way these signal that white Australia is not wholly responsible for ongoing adverse outcomes in Indigenous communities. This is understood and dismissed by progressives as a way of also putting blame on Indigenous people themselves- not always incorrectly. However, the end result is that Indigenous Disadvantage is reduced to the status of political sledgehammer which both sides use to hit each other with, while the real problems remain unaddressed.

This is why Indigenous conservative politician Jacinta Price inspires such pronounced loathing among progressive Australians and within the politically engaged segments of the Indigenous community, and even within remote communities. She rejects symbolic ‘anti-Australian’ identity politics, and instead chooses to raise attention to vexing issues like the real and disproportionate suffering faced by Indigenous women and children at the hands of their male family members- a problem that cannot be neatly attributed to white Australia. One reasonable criticism of Price is that she does so in an untactful way that makes Aboriginal people feel defensive. In doing this, she is seen as attacking Aboriginal people as a collective, even though she is formally advocating for the material interests of the most vulnerable members of her community. Such is the nature of identity politics.

Identity politics neglects the most powerless members of the identity group

The political instrumentalisation of Indigenous Disadvantage means that it has become impossible to discuss Indigenous Disadvantage soberly or honestly without inviting accusations of racism.

As a result, identity politics tends toward enshrining a deranged and perverse political environment which actually preserves and perpetuates a dysfunctional status quo for remote Aboriginal Australians.

The canonical example of this is the utterly broken discourse surrounding Aboriginal children in the care of the state. Indeed, Indigenous kids are vastly overrepresented in the foster care system; one in six Indigenous children received child protection services of some kind in 2021. This overrepresentation, as one learns in Tennant Creek, is proximately caused by intergenerationally broken families, alcohol addiction, and outright parental neglect. Kids who are taken into state care need to be taken into state care, for the incontrovertible sake of their own material and psychological wellbeing. No matter how terrible this intervention is the for child, the alternative is worse.

However, grappling with the awful complexity of this problem is of no interest to Indigenous activists and representative bodies. Their approach is simply to flatly deny the issue of child neglect or abuse in outback Australia, and to frame government intervention as a ‘second Stolen Generations’. Some activists call for policies diametrically opposed to foster kids’ material interests, like the immediate blanket return of all foster children to their families, a policy which would guarantee increased rates of neglect.

This is the psychology of identity politics in action. The sacred imperative is to avoid the group looking bad. Thus, deny the reality of the problem, and frame malevolent external actors as responsible for bad outcomes. Understand this, and you understand identity politics the world over.

I personally witnessed the human consequences of this perverse dynamic when working in Tennant Creek.

Because the government is haunted by the spectre of the Stolen Generations, state agencies responsible for child welfare, like the NT’s Territory Families- which in my experience are poorly staffed and worse run- are highly sensitive to the political radioactivity of intervening, and as a result are extremely reticent to take children from families, no matter how dire the child’s situation. In Tennant Creek, it was generally observed that Territory Families only ever intervened in the very worst cases of child neglect or abuse, and often when it was already too late. This indicates that many children who should qualify for government intervention are ignored and consigned to their neglect.

I knew such children. They would come to school hungry, sleep deprived and traumatised, and the countless welfare reports we made to Territory Families simply vanished into the ether of bureaucratic ineptitude. Even more absurdly, I knew of several instances in which loving adoptive families had made all the arrangements to take a child into their care, only for it all to be undone by a bureaucratic paperwork failure. Thus, in practice, there are likely many, many more children across remote Australia- and likely in non-Indigenous communities as well- who are neglected not only by their families, but by the government.

The government is in a no-win situation. Intervene to the degree it should, and it gets called racist. So, it withdraws from its responsibilities, and children suffer.

To conclude

This broken dynamic is the status quo, and it doesn’t look like changing for the foreseeable future. In fact, Indigenous identity politics is only intensifying in cultural cachet and ubiquity to the point of being widely institutionalised, in light of the ‘Great Awokening’.

This points to an intractably fractured future for Australia, in which it will permanently be held morally hostage by an aggrieved and politically empowered subsection of socioeconomically privileged Aboriginal activists and leaders.

Meanwhile, outcomes for the most disadvantaged Indigenous Australians will continue to deteriorate while their political representatives ensure their plight cannot be ameliorated, and the Australia Day saga will rage on as symbol of the culture war’s fraudulent hollowness.

Thanks for the post Charles,

The domestic violence issue goes back a long way it seems. Here is Inga Clendinnen on experiences in Sydney cove

"Australian interactions seen at close quarters could only erode his hopes for their quick integration into proper British ways of thinking and doing. Worst, and despite British disapproval, men continued to beat their women as of right, and then nonchalantly took them off to the hospital and Surgeon White to have their wounds and bruises dressed. Some women seemed to prefer this treatment to the sedate pleasures available in the colony. At the end of December a young girl had begged to be allowed to live among Phillip’s servants and under his protection, but she stayed for only a few days before, curiosity satisfied, she returned to her old life. Before she left she stripped off all her clothing, retaining only the woollen nightcap she had been given to keep her newly shaven head warm. Phillip drew the unavoidable inference: ‘She had never been under any kind of restraint, so that her going away could only proceed from a preference to the manner of life in which she had been brought up.’ Even young Boorong could not be kept within the settlement, however brutally she might be treated outside it. One day in the new year she came paddling in with another girl who had also enjoyed a spell under British protection, both of them hungry, both of them beaten around the head and shoulders. They said two men known in the colony had beaten them because they refused to sleep with them. And yet, after a couple of days of food and Surgeon White’s care, they paddled away again.

Both the girls’ freedom and their vulnerability were probably the consequence of the disruptions effected by the smallpox epidemic, exacerbated by the proximity of the British camp as an alternative resource and refuge. But Phillip was in no mood for sociological analysis, gloomily commenting, ‘Making love in this country is always prefaced by a beating, which the female seems to receive as a matter of course.’ His comment does not illuminate the case—the girls were beaten precisely because they said no—but it captures his increasing despondency.”

From Dancing with Strangers

A sober but entirely accurate reflection on the intractable issue of indigenous disadvantage in Australia.