The Mythology of the Voice

The Voice Referendum is the culmination of our ideologically imposed inability to reckon with the reality of Indigenous disadvantage.

This Saturday, Australians will decide whether to amend the nation’s Constitution to include an Indigenous body that makes non-binding representations to Parliament on any matters relating to Indigenous Australians. This body is called the Voice to Parliament, and it is sold to the public as the solution to one of Australia’s most enduring and vexing problems: that of Indigenous Disadvantage.

Indigenous Disadvantage has come to occupy permanent and outsized space in the arenas of Australia’s public discourse, in the columns of its broadsheets, in the minds of its citizens, and in the budgets of its governments. The mission to ‘Close the Gap’ between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians has long enjoyed absolute and unanimous support across Australia’s political frontlines, and in 2023 represents less of a policy issue than a spiritual crusade. This crusade is about more than improving outcomes in Indigenous communities; it is about rectifying the moral stain at the heart of the modern Australian state- that of colonisation.

One cannot understand the present moment without understanding the guilt which defines the way Australia looks back upon its colonial inception, and by extension its Indigenous people. This guilt manifests itself today through the enforced insertion of Indigenous symbolism into every domain of public life, best exemplified through Acknowledgements of Country which are as ubiquitous as they are often pointless.

This political-cultural phenomenon can be explained to an outsider (or to a confused Australian, of which there are many) in the following way: in the last decade or so, Australia’s intellectual and cultural establishment has embarked on the project of redefining Australia’s national identity, by placing disproportionate emphasis on Indigenous culture and symbolism- or to borrow the language of academese, by centring ‘First Nations’ people, culture and ‘ways of knowing’ at the heart of modern Australia.

The horror we feel at the act of the colonisation and displacement of Australia’s pre-colonial Indigenous societies is in many ways an inevitable outcome of our distance from the act of colonisation itself. As we as a nation become more temporally removed from the manner of our inception, we naturally identify less with it, and even begin to identify in opposition to it. As a result, for many Australians today part of what it means to be a good person is to signal publicly that one is pro-Indigenous. Today, this means supporting the Voice to Parliament- or opposing it for not having enough power, if you want to signal that you are really pro-Indigenous.

Beyond serving as a therapeutic device for alleviating the guilt of educated Australians, the Voice to Parliament is propelled by its claim to be the solution to the enduring problem of Indigenous Disadvantage. That Australia’s remote Indigenous communities are dysfunctional and disadvantaged, and that Aboriginal people suffer from worse life outcomes, is one of Australia’s most well-established talking points.

This talking point was my lived reality. Until recently I spent several years living and working in the remote town of Tennant Creek, infamous for its position at the frontline of Indigenous Disadvantage. I was able to witness the profound dysfunction which defines remote community life, and the way in which the government and its myriad services fail to ameliorate this dysfunction, and often even enable it. It is safe to say that I am still grappling with my experience in Tennant Creek.

Indigenous Disadvantage as a talking point is notable for two things. Firstly, it is notable for how little familiarity the Australian public has with it. Most Australians have never seen the reality of life in a community or town camp. As a result, Indigenous Disadvantage is poorly understood, and exists in the public consciousness as an abstract problem which occurs far away in the desolate expanses of the Australian outback.

The second notable feature is that Indigenous Disadvantage has defied everything thrown at it. It has seen off decades-long attempts by successive Australian Governments to fix it; it has swallowed the many tens of billions of dollars thrown its way; it has spawned the erection of an Aboriginal affairs industrial-complex which cannot eradicate it; it has thwarted the self-determination movement; it has mocked the Closing the Gap targets. This crystallises the paradox of Indigenous Disadvantage: for all the colossal amount of effort, programs, and money the government expends on improving Indigenous outcomes, Indigenous outcomes have largely deteriorated if they haven’t stagnated.

Out of this well of eternal disappointment has emerged the central idea underpinning the Voice: that the solution to Indigenous Disadvantage lies in Indigenous hands. Australian governments must delegate control, authority and decision-making power to Indigenous communities and their leaders, who are in the best position- both morally and practically- to make decisions for themselves, and in doing so Close the Gap.

The Voice is steeped in this idea. In the words of Minister for Indigenous Australians Linda Burney:

“This is not about culture wars, this is about closing the gap. […] It is about making it practical and making a practical difference.”

And herein lies the central myth responsible for the incoherence of the Voice movement: that Indigenous communities suffer from a lack of consultation or self-determination, and that changing this will improve outcomes.

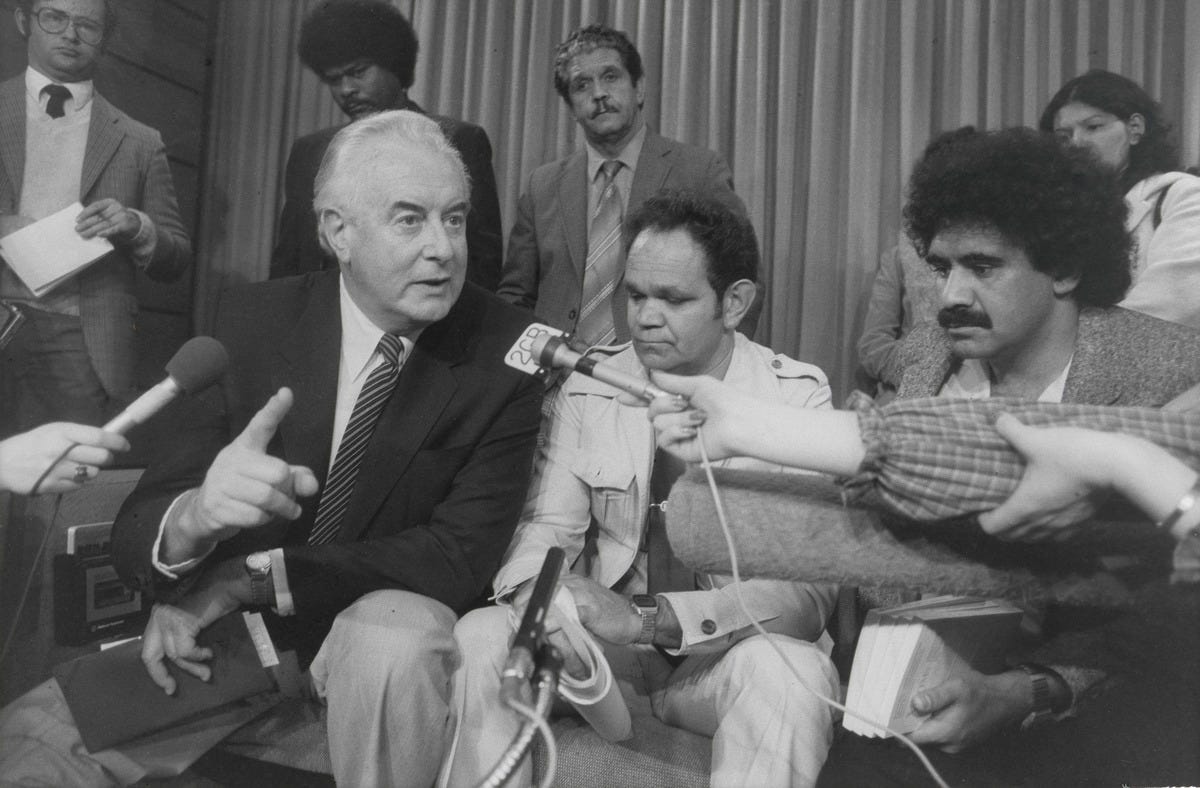

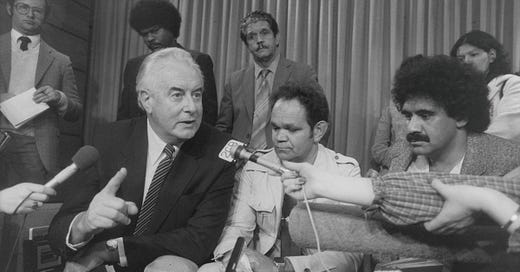

Those who believe in self-determination as the solution to Indigenous Disadvantage are many, and they are misled. In reality, self-determination was introduced as the reigning policy paradigm for Aboriginal affairs by the Whitlam government in 1972.

“One of the most interesting exercises upon which we have embarked has been to consult the Aboriginal people themselves. We have done this because we believe that for too long the Aboriginal people have been placed in the situation where people have done things for and to them but never with them by consultation.”

These are the words not of Anthony Albanese, but of Gordon Bryant, Minister for Aboriginal Affairs… in 1973.

One of the most interesting revelations from this era is that in 1973 the Whitlam Government even set up a body that functioned almost identically to the proposed Voice: the National Aboriginal Conference (NAC). This was a body of elected Indigenous representatives with the explicit purpose to advise the government on all policies and issues relating to Indigenous peoples. Sound familiar?

The NAC was disbanded by the Hawke government in 1985 after a decade of lamenting that its recommendations were not binding, advocating for treaty (it is responsible for the popularisation of the term makarrata), infighting, and financial mismanagement. NAC was followed by the better known Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), which again operated (poorly) under the framework of Indigenous self-determination and consultation until its demise in 2005.

To reiterate: decision-making power already has been shared with Indigenous communities and leaders. The ‘voice’ experiment has been run. The NAC and ATSIC were created, Native Title and Lands Rights have been recognised, myriad peak bodies, Land Councils and corporations have been created explicitly to represent community interests; separate programs, agencies and services have been set up to cater exclusively to Indigenous people; there are 3,521 Aboriginal corporations operating today.

Community consultation is the approach du jour; it is the approach de hier. This truth shatters the myth buttressing the Voice to Parliament. Giving traditional owners jurisdiction over their land and Indigenous communities greater say in how they are run has been the modus operandi for the last fifty years, and it hasn’t Closed the Gap. There is no reason to believe that the Voice will be any different.

Aboriginal leaders themselves are not immune to this observation. Take Michael Mansell:

“The Yes campaign are trying to convince the country that the prime minister, state premiers and peak organisations cannot reduce and close the gap, but an advisory body that meets a few times a year in Canberra is going to be able to do it.”

The fact that it is not widely known in contemporary public discourse that self-determination has already been tried and that it failed to ameliorate Indigenous Disadvantage is reflective of the highly constrained ideological landscape in which Indigenous issues have existed for the past fifty years. Successive generations of activists have colonised Australia’s university, media, and government departments to create a powerful normative orthodoxy which dictates the establishment position on all Aboriginal affairs. This politically correct orthodoxy is the water in which we swim. It is unable to correct itself, due to its fundamentally moralistic nature.

Which leaves us today, recycling ideas from 1973, choosing to pretend that self-determination or consultation has never been tried, unable to reconcile with the utter mess that has been created across Australia’s interior.

It is for this reason that it remains an open question whether Linda Burney really believes it when she proclaims that the Voice will Close The Gap. The notion is absurd on its face to anyone who has grappled honestly with the reality of Indigenous Disadvantage, or with our failed history of attempting to remedy it.

The true causes of Indigenous Disadvantage lie beyond the scope of this essay, but an honest reckoning would require nothing less than an ideological revolution upending a half-century of failed establishment orthodoxy.

In the end, for many Australians who are voting Yes, whether or not the Voice works does not matter. It is beside the point. The Voice exists as yet another symbolic gesture of repentance and reparation which defines the nation’s relationship to its Indigenous minority. And for the Indigenous elite who sponsor it, it represents the assertion of the power of Aboriginal identity politics for the sake of asserting power.

Regardless of whether the Australian people vote Yes or No, Australia is condemned to its guilt.

****

How thoughtfully researched and how well articulated. Bravo!